Dr. Michael S. Blekhman, PhD (Linguistics)

Deceased may 2022.

President, Lingvistica ’98

Inc.

President, Lingvistica b.v.

Dongen, The

E-mail: ed@semanta.nl

Tel: +514 9955366

Linguistic

Resources by Lingvistica ’98 Inc.

Lingvistica ’98 Inc. is a world-known

developer and supplier of linguistic resources for Slavic, West European, and

Asian languages:

q word lists

q lexicons

q word frequency

lists

q lexical

dictionaries

q grammatical

dictionaries

q onomastica dictionaries

q morphological

analyzers and synthesizers

q text corpora

q translation

engines

Since 1998, we have provided

linguistic resources and solutions to various companies all over the world,

such as SYSTRAN (USA), France Telecom (France), New Mexico State University

(USA), LogoMedia Corporation (USA), and many others.

We develop linguistic resources and supply them to our customers.

Here is a concise list of our linguistic resources and solutions:

- Word lists for Azerbaijani, English, French,

German, Polish, Russian, Turkish, Ukrainian.

Under way: Arabic, Persian (both unvoweled),

Dutch, Pashto.

- Grammatical dictionaries, i.e. words with

grammatical features: English, German, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian. Under

way: Dutch, Pashto.

- Numerous bilingual dictionaries including

Slavic and West European languages, in particular, a comprehensive FrenchóGerman

dictionary. Under way: EnglishóDutch; EnglishóPashto;

EnglishóAlbanian.

- Automatic translation engines.

- Morphological analyzers & synthesizers.

- Software for finding words absent in the

dictionaries: English, German, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian. Under way:

Dutch. – See Annex 1 below.

- Software for finding potential proper names:

English. – See Annex 2 below.

- Russian text corpus - over 1 GB.

- On-line word translation technology – see Annex

3 below.

Annex 1.

Web

Mining for MT Dictionary Acquisition

Lingvistica b.v.,

a language engineering company based in

·

English from and to Russian

·

English from and to Ukrainian

·

English from and to Polish

·

German from and to Russian

This translation family as such is described in detail elsewhere.

In the framework of the above project, we have developed a subsystem for

web mining, finding words missing in PARS dictionaries and adding those words

to the dictionaries. This task seems to be extremely important for keeping MT

systems updated taking into account the fact that Internet provides “new” words

weekly if not to say daily. Those words are proper names, such as euro, bin Laden, talib,

etc., and “conventional” words, especially frequently found on Russian and

Ukrainian web pages: the fast developing and changing socio-political life in

the ex-Union introduces new phenomena and thus brings to being new words.

What is very peculiar is that such words are often already present in

the MT system dictionaries with wrong translations, which is even worse than

having no translation at all. A vivid example is bin in bin Laden.

At the same time, these new words often play the key role in the texts

to be translated. We have had dozens, if not hundreds, of Internet pages

translated by PARS and made sure that the resulting translations look

absolutely devastating if the keywords have not been translated at all or,

which is even worse, translated in the wrong way.

More than that, such problems are also characteristic of the

professional dictionaries used for machine translation, or, as they are often

called, “technical” dictionaries. It is well known that new words appear

especially often in such subject areas as electronics, computers, and some

others, and ignoring them makes technical dictionaries obsolete, useless and

even misleading.

Our experience makes it evident that it is practically impossible to

keep track of those words and thus make a translation system efficient enough

without having an automatic tool for gathering the new words, preferably on a

regular basis.

In order to considerably increase MT system efficiency, we have

developed what we call MTI (Machine Translation for the Internet) –

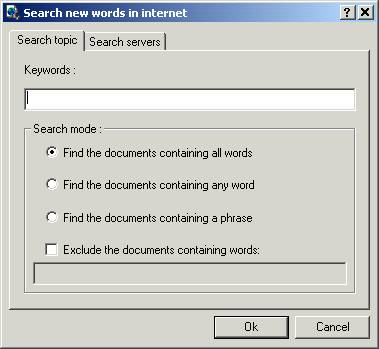

software for gathering new words from the Internet. MTI operates in 2 modes:

·

For adding words to the general dictionary, it

performs word search on portals; the portal address is introduced by the user.

The latter also selects the translation direction, dictionaries used in the

translation session as well as the dictionary into which new words will be

entered.

·

For adding words to the technical dictionaries, the

user performs topic-oriented search. For doing this, he/she introduces the

search server name (such as AltaVista, Google, etc.) and then the search

inquiry.

The search inquiry is a Boolean expression (string of keywords) with

the AND, OR, and BUT operators used as logic connectives.

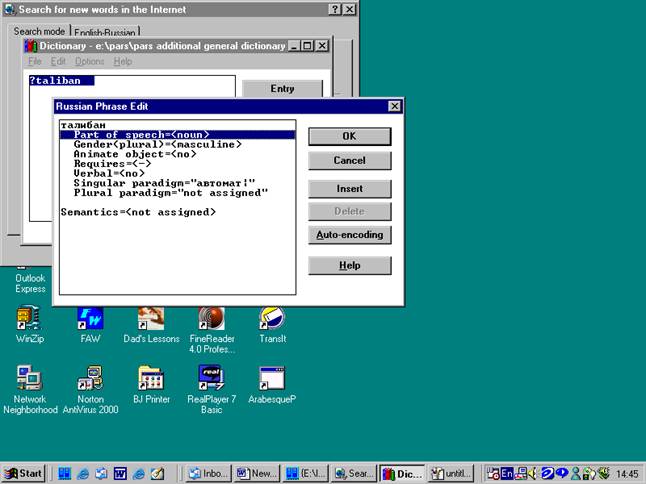

After the MTI program is started, it turns on the corresponding PARS

translation engine on (for example, English to Russian), which translates the

corresponding pages, moving from link to link thus translating the whole web

site indicated by the user. Each word not found in the dictionaries being used

in the translations session is added to the dictionary marked in MTI as the one

into which the new words should be written. In the PARS dictionary entry, such

a word is entered beginning with a question mark.

The user adds the translation(s) and assigns grammatical and semantic

characteristics (if any). The PARS “automatic encoding” option makes assigning

grammatical features comparatively easy.

A double click on the source word automatically deletes the question

mark and puts the dictionary entry in the right place in the dictionary.

Our tests have proven technology efficiency. For example, it took the

MTI program several minutes to process over 50 links provided on the CNN.COM

web site and add about 100 new words to the PARS

Comprehensive Dictionary. Taking into account that the latter is really big (it

comprises about 100,000 English entries), its manual updating is far from being

an easy task, while MTI added 100 new words to such a huge lexicon within

minutes.

Annex 2.

Web

Mining for Proper Name Dictionary Acquisition

- General

Proper names are an important linguistic resource to be used in all kinds of language engineering products, such as information retrieval systems, machine translation systems, and many others. The problems about them are their huge number and the fact that new proper names appear regularly, if not to say daily, in numerous Internet databases, which makes it necessary to keep track of the new proper names and add them to the onomastica dictionaries.

Our

experience makes it obvious that there is no reliable way of manual onomastica

dictionary acquisition. To make this important and labor-consuming work

efficient and feasible, Lingvistica b.v. has developed automated proper name

dictionary acquisition software. The project has been made possible due to the

financing from the Computing Research Laboratory of the

Lingvistica’s

collaboration with NMSU CRL in 1999-2000 resulted in the development of a

series of onomastica dictionaries based on the CRL list of 200,000 English

proper names. The language pairs covered are: English to Arabic, Chinese,

Japanese, Persian, Russian, Spanish, and Turkish. In 2001-2002, we are supposed

to extend substantially the existing English onomasticon by providing an

efficient tool for regular, everyday web mining and adding English proper names

to the existing onomasticon.

- System description

The system consists of 2 modules:

- Content Replicator – a program that does web mining and extracts potential proper

names for further manual post-editing;

- Names – a program for manual post-editing of the potential proper names gathered

by the Content Replicator from the web databases; the post-editing

is performed by a human lexicographer.

The final

result is the onomasticon – a text file of proper names, in which the names

have semantic markers assigned by the human lexicographer. Fig. 1

illustrates the general scheme of onomasticon

acquisition.

Fig. 1 General scheme of proper name dictionary acquisition

The arrows

symbolize Internet data processing, while the squares illustrate actions made

as well as the software modules used.

Here is

what each of the system modules does.

The Content Replicator processes a web site and creates a local site image on the lexicographer’s hard disk. When doing so, the Replicator transforms the HTML pages into plain Unicode text without pictures, flashes, links, etc.

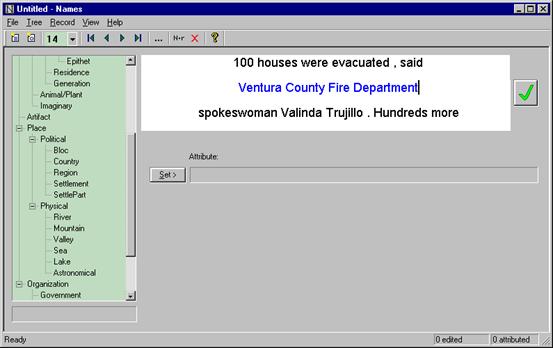

Potential proper names are then automatically gathered from the resulting text files using the Names program and imported into a special database, each name accompanied with a context determined by the lexicographer: a fixed number of words to the left and to the right of the name, or the whole sentence (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Importing potential proper names into the database

A word or string of words is considered a potential proper name if it is written with capital letters and surrounded with nominative group boundaries or non-capitalized words.

The experience shows that at least 60% of the automatically selected strings are not proper names, which makes human post-editing absolutely necessary. Besides deleting irrelevant strings, the lexicographer assigns semantic markers to the proper names selected. In doing so, the lexicographer uses the Ontology semantic tree developed at NMSU CRL. The context helps the lexicographer determine which marker should be assigned to the name. Fig. 3 illustrates this technology. In the screenshot, the potential proper name is marked blue, while the contexts (left and right – respectively at the top and at the bottom) are black. The semantic tree is in the left part of the dialog box.

Fig. 3. The Names

program dialog box

The

lexicographer can use the following commands:

![]() Skip- skips previously processed names

Skip- skips previously processed names

![]()

Normalize – delete dots

and commas leaving characters only

![]() Delete – delete current record

Delete – delete current record

![]() First record – move to the 1st

record in the database

First record – move to the 1st

record in the database

![]() Previous record – move to the last record

in the database

Previous record – move to the last record

in the database

![]()

Next record – move to the

next record in the database

![]() Last record – move to the last record

in the database

Last record – move to the last record

in the database

The

lexicographer can edit the potential proper name or delete it. After editing,

he/she assigns a semantic attribute to the proper name in the Attribute

box and saves the final entry in the database provided that such an entry is

not present there yet. Fig. 4 illustrates this box if the proper name has the

attribute Valley.

The above

software has proved quite reliable and increased proper name dictionary

acquisition dramatically. The experience shows that one lexicographer can add

up to 1,000 proper names to the dictionary during a full day of work. Onomasticon acquisition is under way at the Canadian office

of Lingvistica b.v.

Annex 3.

Web translation aid

![]() Sergei Nirenburg,

Sergei Nirenburg,

sergei@umbc.edu

This projects

deals with Ukrainian as well as Asian languages, such as Arabic, Pashto,

Persian, and others. We are planning to develop a user-friendly translation tool

that will let the customer grasp the general idea and subject area of the text

on the web page, quickly and easily.

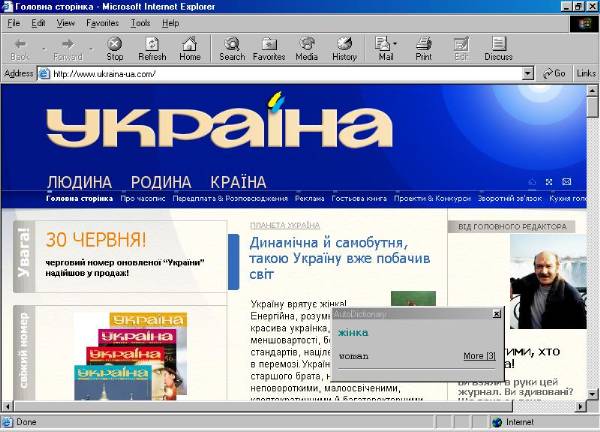

The customer

will open a web page displaying a text in an unfamiliar language. Even the

script may be a puzzle. By pointing the cursor at any word on the page, the

user will immediately get its English translation in a separate window under

the source word.

Then, by double

clicking the translation, he/she will get all the translation variants.

We have

developed a prototype of this system for the Ukrainian language.